|

| Loh mee |

Loh mee (also lor mee) is characterised by its thick, spicy (not hot) gravy. The noodle soup I had had a distinct hoi sin taste to it, presumably from five spice. It was augmented with pieces of mock meat - roast pork, char siu pork - and crunchy fried bits that would be crispy lardons in the meat equivalent.

|

| Fish head bee hoon soup |

The 'fish heads' turned out to be thin and crispy fried slices of tofu wrapped in nori. They were served in a clear gingery broth, which K declared "delicious".

Our intention today was to visit places of worship of the four major religions on the island, each of which is represented on Jalan Masjid Kapitan Kling - locally referred to as "Harmony Road", but also known under its previous name, Pitt Street.

The road is named after the mosque (masjid) at the southern end, which is where we started.

|

| Masjid Kapitan Keling |

Our search for someone to enlighten us about both building and the beliefs of the worshippers who attend it was somewhat thwarted. The mosque information services are closed on a Sunday, so we visited the building. K had to don a fetching lilac cloak - complete with hood - for reasons of decency, and wouldn't be let in at all were she menstruating, lest she frighten the horses.

|

| Chinese lucky ingots |

The Hindu Sri Mahamariamman temple seemed to be closed and in a state of renovation, which will make it difficult to celebrate the upcoming Thaipusam festival on 3rd February.

|

| Kuan Im temple |

The Buddhist temple of the Goddess of Mercy (Kuan Im) was the busiest site we visited, with many worshippers praying and lighting incense sticks. Aside from days of particular significance, a good handful of worshippers can be seen at the temple at all times of day throughout the week, in contrast to the Muslim five times daily prayer or Christian Sunday worship.

|

| Large incense sticks |

In the courtyard several enormous braziers were consuming oversized incense sticks the width of a man's arm and twice its length. I presume the intensity of activity will only increase as Chinese new year in February approaches. The streets surrounding the temple are currently being festooned with red lanterns in preparation.

The Chinese temple mixes Taoist and Buddhist images, although this is often a tricky distinction, as Kuan Im (also Guanyin) is both a bodhisattva, who eschewed nirvana in order to free the populace from suffering, and is also revered as a Taoist immortal. Alongside Kuan Im stand representations of Fu, Lu, and Shou - Taoist Gods of Prosperity, Status, and Longevity, respectively - and depictions of the characters from the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West.

|

| Four heroes from Journey to the West |

Unfortunately, despite the crowds at the temple, we found no ear to hear our questions about Buddhism and Taoism.

|

| St George's Church |

It was a similar story at St George's Church, which was shuttered up after the morning's services. However, this is where we needed the least orientation, as K is well versed in Christian beliefs. In fact she attended a local Methodist church this morning, the sermon of which apparently concerned 'witnessing'.

|

| No, seriously |

I have always found witnessing of one's faith an unusual use of the word, and for many people I suspect it brings to mind the door-stepping of Jehovah's Witnesses. This is an extreme form of sharing one's beliefs, but I imagine that most people can empathise with the urge to share something about which one is most passionate. To someone who has discovered a source of such joy, hope and pleasure, it seems inconceivable that others wouldn't also derive similar satisfaction, if only they knew about it. Any reservations they have might easily be disabused, one imagines.

With questions of personal taste, persuasive argument is where it ends, but articles of faith can often inspire more zealous opinions. If one believes that one's views are backed by an unquestionable, inerrant source of truth, then one can become deaf to any counter-argument. Self-righteous and arrogant rhetoric is surely the worst way to promulgate a message (see Richard Dawkins), which is why the best advocates witness through actions as much as words.

|

| Is this the right place for an argument? |

The best, but most difficult, way to approach an argument is in an open way and in a spirit of truth-seeking, accepting that one's currently held beliefs may not be correct, rather than seeking to convince the other, 'ignorant', party of their error and to bring them around to one's own way of thinking.

However, uncertainty is scary. Admitting that one's own beliefs or way of life aren't necessarily right requires bravery. We err towards, wittingly or otherwise, disregarding contradictory facts and retelling only those that fit with our personally espoused theory, in an effect known as conformation bias.

But, a lack of information concerning opposing or different theories can lead to defensiveness, which arises from fear. Fear that we may be wrong, and that others may be right. And fear, as Yoda so rightly pointed out, leads to suffering. Lack of information only strengthens our own beliefs, as any others lack depth or substance to be believable. Hence, it becomes easier to question, to misunderstand, and even to despise others who hold such obviously untenable opinions.

And so, to have moral certitude, one might want to subscribe to a specific rendering of The Truth.

History abounds with scripture and written doctrine, from the Upanishads and the Pāli Canon, to the Torah, Bible and Koran. These sacred texts are believed by some to contain revealed truths, hitherto unknown to Man, and in certain cases are believed to be inerrant in word. Subscribing to the teaching of any one of these truths may or may not be exclusive with the belief in the veracity of any of the others. However, this is not what is interesting (at least to me).

Rather than arguing doctrinal specifics, it is far more fascinating to discern the similarities between these documents - some written many centuries apart, by different hands in different lands.

Whether codified and documented or perpetuated through oral narrative and ritual custom, most religions offer a metaphysical explanation for 'how things are': How was the world created? What is the purpose or meaning of life? What happens after we die?* They may explain supernatural events, such as miracles, apparitions, and unlikely coincidences.

* Buddhism notably refuses to expound on these questions, which are considered unanswerable and the subject of counterproductive speculation.

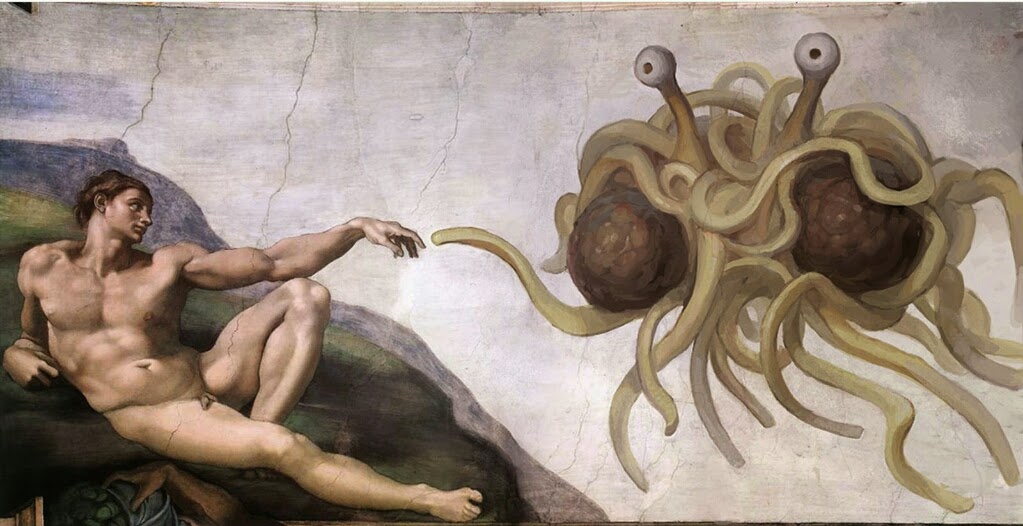

To my opinion, none of the explanations to the above questions put forward through the years is more inherently believable than any other explanation. Some explanations have gained a certain legitimacy simply with the passing of time, but make the same unfalsifiable claims as parody religion Pastafarianism.

|

| Touched by His noodly appendage |

Individuals and groups have invented or received many colourful explanations to the above questions throughout history. Envisaged creators and rulers of the world and everything in it range from a merciful and benevolent Father God, through a pantheon of feuding deities and demi-gods meddling in the life of Man, to spirits possessing everything from the wind to the sea, which must be appeased through customary ritual.

Explanations for how reality came to be venture that it was the product of a dismembered divine being, or manufactured within a week by a single lonely creator, or even that there have been several worlds before this one whose people were variously destroyed by jaguars, hurricanes, and rains of fire.

Regarding the afterlife, the general nature of this depends on one's conduct in the earthly life, and one may anticipate living out eternity in a heaven or hell, whose precise characteristics have been the subject of thousands of colourful descriptions, or perhaps being reincarnated endlessly as greater or lesser beings, until one's deeds allows escape from this cycle.

While wonderful, creative, mostly beautiful and sometimes fearful descriptions, these explanations seem to me to be mere conjecture. There is no profound truth.

I suppose this is part of having 'faith'. To believe, in the face of no or unverifiable evidence, in the truth of a particular explanation for supernatural phenomena.

The need for such explanations is clear. Life is wonderful; to describe it in banal terms seems disrespectful, so we wrap it up in colourful description. Metaphor allows us to describe forces and processes for which normal language is inadequate or simply seems too prosaic. We anthropomorphise natural occurrences (e.g. Death) to make them more understandable. Such descriptions are rich and wonderful and have influenced and coloured the art, festivals, clothing, stories and way of life of each civilisation that created them. I would not wish to get rid of them. But we should not confuse the metaphor with reality.

|

| Confucius say |

Many sage individuals have given wise advice to the people of their time, some of which has proved relevant for generations to come and has entered into the status of tradition, being repeated and followed fervently among a particular group of people and their descendants.

Personally I don't believe any of these teachings have been inspired by anything more divine than the sages' own minds, which is incredible enough. To lead, inspire and to give hope to people for generations is something to be respected. But we should not lose sight of the fact that, no matter how wise, the teachings are advisory only. Punishing, judging and condemning others for not following arcane doctrine is perverse. By all means take any set of rules of your choosing as a personal guide for how to live your life, share them with others if you feel they are particularly expedient, but do not hold others to your same standards and be tolerant of other, possibly contradictory, explanations for the phenomena you observe.

|

| A pretty clever patent lawyer |

Instead, let's focus on a common set of tenets. Harmony Road inspired me to see how four quite distinct groups of people, each with an ostensibly different faith, can co-exist and share in their common beliefs. It's like a wonderful Venn diagram, in which each group is represented by a circle. The overlapping part of these circles represents those beliefs that are the same - even though they may use different names or language to explain them - and is greater than the parts that don't overlap. You will have to imagine this diagram too, as I don't have the creative wherewithal to realise it.

|

| John Venn. A proper Yorkshireman. From Hull |

It doesn't matter whether your truth is a personally held belief, a divine revelation through a prophet, such as Jesus, Muhammed, or Moses, or wisdom dispensed by an enlightened individual, such as Lao Tze, Gautama Buddha, or Confucius. It doesn't matter whether you believe in one God, many deities, or in no particular creator, in afterlife, reincarnation, or immortality, in miracles, angels, or jinns, in salvation, moksha, or nirvana. We may use tradition and rituals as comfort, as a way to fit in with our family or community, or as a means to remind us to act in a manner that is in accordance with a way of life to which we aspire, but which we do not inherently tend, such as prayer, meditation, or fasting.

Use whatever means you must to be the things that make life good for you and for others: Love everyone, be happy, be generous, be grateful, be awed by people and nature, and believe what you like about the things you can't see or prove, but please don't try to make others believe the same or judge them because they think differently.

Seeing so many different places of worship in close proximity - distinct in their rites and practices, but respectful and harmonious - cemented for me the multi-cultural aspect of Penang. A wonderful example of this is the mixing of immigrant Chinese and Malays, which created a new people, new food, art, and language.

We visited the Peranakan Mansion - a beautifully restored 'Baba Nyonya' residence - which was occupied for two generations. While the shell of the building remained, the inside was gutted, so the contents was sourced and is indicative of the actual furnishings and decoration. The original owner of the building gained his fortune through trading in tin and opium.

As we saw from the 'self-made men', Yeap and Cheong, vast fortunes were there to be made by those with the nous. The Peranakan culture developed to use this wealth in a slightly disgraceful yet fascinating opulence.

The Peranakan 30-day weddings with all their attendant trappings, which we saw at the Penang Museum, were only the surface. The Mansion contains the everyday items of Baba-Nyonya life, the extravagance of which centres around the dress and accessories for the Nyonyas.

|

| 'Baba' and 'Nyonya' |

The Peranakan tended to marry young - both the bride and the groom - often in an arranged marriage. The groom's family sought a girl that can demonstrate prowess at cooking and sewing - preferably to the exclusion of all else, such as a social life. Such unwavering dedication to craft - and, by extension, unerring devotion and compliance to a suitor - is most aptly embodied by the hand crafting of 'bead shoes', which take the little nyonya anywhere between 3 to 6 months to sew miniscule beads onto the shoe uppers, during which time she barely leaves the house. In return, the bride's family expected wedding dowries that could sink a ship.

|

| Gold dolls' house furniture |

The museum display houses such gilded everyday items as solid gold dolls house furniture and dinner places set with silver and crystal decanters.

Tradition surrounding death was as rigorous and as extensive - if less ostentatious - as marriage. Mourning wardrobes comprised clothes of a single colour only -black for the first year of widowhood, blue for the second, and green for the third - and, of course, the widow was expected to wear plain old silver and pearl jewellery rather than the usual gold bling as a sign of respect.

The one aspect of tradition that I found difficult to excuse, as it involved inflicting suffering on someone else - in this case a child - was foot binding. The deformed feet, apparently considered beautiful, were the result of tight binding from an early age. It is said that the girls, women and families were proud of this tradition.

After a day of cultural enrichments and theological - some might say iconoclastic - debate among ourselves, we needed sustenance.

Around the corner from the Peranakan Mansion we found Sri Ananada. This is a pure vegetarian Indian that features cuisine from Chettinad including traditional dishes using mock meat. However, we eschewed a fake chicken tikka masala in favour of a couple of thalis to circumvent choice paralysis and get a wider selection.

|

| South Indian thali |

We ordered a South Indian thali and a North Indian thali. The southern style had greater emphasis on lightly spiced vegetables (carrots, green beans, cabbage) and dals (spicy red, mild yellow, and a thick and salty tarka). The northern version had 'chicken' palak, and some unknown but tasty curries.

|

| North Indian thali |

In a fit of over-ordering that comes upon me in Indian restaurants, we also had uttapam - a thick rice flour pancake topped with onions and chillies - and murtabak - a roti stuffed with vegetables. Both were individually served with a portion of vegetable curry and were a meal in themselves.

We rolled fatly home only to find that Steven had left us a gift of apple pie. Such delicious torture.

No comments:

Post a Comment